As a real estate realtor and serving more than 10 years in the real estate field, I will share my knowledge about probate property, its process, and issues. You can comment on me if any points are missing. But I try to cover all aspects in this article.

Probate property means anything a person owned in their name only when they died, like a house, car, or bank account. Since no one else is listed as the new owner, the court has to step in to make sure it goes to the right person. This process is called probate. It can take time and cost money. Things like joint accounts or homes with co-owners usually skip probate. That’s why many people try to plan ahead to avoid it.

Understanding the Basics of Probate

Definition of Probate

Probate is the legal process by which a deceased person’s estate is administered. It involves verifying their will (if one exists), identifying heirs, appraising property, settling debts and taxes, and finally distributing the remaining assets. Think of it as the court’s way of making sure everything is handled fairly and according to law.

If the deceased had a valid will, the probate court ensures that the instructions in the will are carried out properly. If there is no will, then the estate is distributed according to state laws—usually to close relatives. In either case, the court oversees the entire process, which is why probate is such an essential legal mechanism in estate matters.

Probate isn’t always a bad thing—it provides a structured way to wrap up someone’s financial life. But it can be slow, public, and costly. That’s why it’s important to understand what probate is and how it applies to different types of property.

Purpose of the Probate Process

The primary purpose of probate is to ensure that the deceased person’s debts are paid and their remaining assets are properly distributed. The court’s involvement helps prevent fraud and protects both creditors and heirs.

Let’s say someone dies with a lot of debt. Probate gives creditors an opportunity to make their claims against the estate before the assets are handed out. This protects the interests of people and businesses who might be owed money. Likewise, probate ensures that the rightful heirs receive what they are entitled to, reducing the chances of disputes or legal challenges.

Another goal of probate is transparency. Since it’s a public process, anyone with a legal interest in the estate can see what’s happening and voice their concerns. This openness helps build trust and fairness in the process.

Who Handles Probate? Executors and Courts

Once someone passes away, the person who steps in to manage the estate is known as the executor (or personal representative). If the deceased left a will, it usually names an executor. If not, the court appoints someone, typically a close family member.

The executor’s job is no small task. They must locate all the deceased’s assets, determine which ones are probate property, notify creditors, pay debts and taxes, and then distribute the remaining assets to the beneficiaries. They also need to keep detailed records and may have to submit reports to the probate court.

The probate court, on the other hand, oversees the entire process to ensure the executor is doing their job correctly. The court can intervene if disputes arise or if someone challenges the will. Together, the executor and the probate court act as checks and balances to make sure the estate is settled lawfully and fairly.

Probate vs. Non-Probate Property

One of the most important distinctions in estate planning is understanding the difference between probate and non-probate property. Why? Because only probate property goes through the court system, which can be a lengthy and expensive ordeal.

Probate property includes:

- Real estate held solely in the deceased’s name

- Bank accounts without a joint owner or named beneficiary

- Personal belongings (jewelry, furniture, collectibles)

- Vehicles titled only in the deceased’s name

- Stocks and bonds not held in a trust or designated to a beneficiary

Non-probate property, on the other hand, passes automatically to another person by operation of law and avoids the probate process. Examples include:

- Life insurance policies with named beneficiaries

- Jointly owned property with the right of survivorship

- Payable-on-death (POD) and transfer-on-death (TOD) accounts

- Assets held in a living trust

Understanding these categories helps families prepare better and minimize the burden of the probate court.

Common Types of Probate Property

When you hear “probate property,” think of anything that was solely owned by the deceased and didn’t have a clear, legally recognized way to pass to someone else. Here are some of the most common types:

- Solely Owned Real Estate: Homes, land, or other property without co-owners.

- Unregistered Bank Accounts: Savings, checking, or investment accounts without POD designations.

- Personal Property: Furniture, electronics, artwork, and heirlooms.

- Vehicles: Cars or boats that are only in the deceased’s name.

- Business Interests: Shares or ownership stakes in private companies.

These assets require a probate court’s green light before they can be handed over to heirs, which makes them subject to probate delays, fees, and possible disputes.

Examples of Probate Assets

To clarify, here’s a simple table showing what typically falls under probate:

| Asset Type | Probate or Non-Probate | Explanation |

| House (in sole name) | Probate | Needs court approval to transfer ownership |

| Joint bank account | Non-Probate | Passes directly to co-owner |

| Retirement account w/o beneficiary | Probate | Becomes part of the estate |

| Life insurance (with beneficiary) | Non-Probate | Proceeds go directly to the named person |

| Car (sole ownership) | Probate | Title transfer needs probate |

Knowing these distinctions is key to effective estate planning and managing expectations during inheritance.

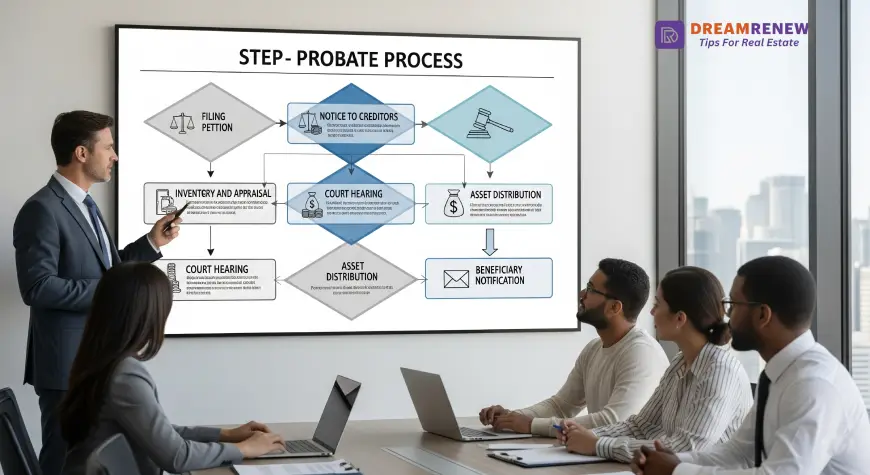

The Probate Process Step-by-Step: Filing a Petition with the Probate Court

The very first official step in handling probate property is to file a petition with the probate court. This step essentially opens the case and notifies the legal system that someone has passed away and their estate needs to be settled. The petition is usually filed in the county where the deceased lived at the time of death.

Who files the petition? If there’s a will, the named executor does it. If there’s no will, a close relative (often the spouse or adult child) steps up and requests to be appointed as the estate’s administrator. The court then reviews the application and, if everything checks out, officially appoints them to manage the estate.

This filing includes some essential documents, such as:

- A certified copy of the death certificate

- The original will (if there is one)

- A list of known heirs and beneficiaries

- A preliminary inventory of the estate’s assets

Once filed, a court hearing is scheduled, and notices may be sent to interested parties—including heirs, beneficiaries, and potential creditors. If there are no objections, the court will grant what’s called Letters Testamentary (for executors) or Letters of Administration (for administrators without a will). These documents give the executor or administrator the legal authority to act on behalf of the estate.

From here on out, this person becomes the estate’s representative and must manage everything responsibly. They’re not just writing checks—they’re stepping into the legal shoes of the deceased to tie up all financial loose ends. It’s a powerful and serious role, and the court stays involved to make sure they don’t abuse that power.

Identifying and Inventorying Probate Property

Once the court grants authority, the next major task is taking stock of what’s actually in the estate. This involves identifying and documenting all the probate assets—essentially making a master list of everything the deceased owned that must go through probate.

This includes:

- Real estate not jointly owned or in a trust

- Bank and investment accounts without beneficiaries

- Vehicles and recreational equipment

- Furniture, art, jewelry, and other personal items

- Business interests, intellectual property, and unpaid income

The executor (or administrator) is required to file this inventory with the probate court within a certain timeframe—usually a few months. This step is more than paperwork; it sets the foundation for paying debts and distributing assets. The court needs to know exactly what the estate is worth.

Depending on the size and complexity of the estate, the executor may need help from professionals like appraisers, accountants, or lawyers. For instance, if the deceased owned a valuable art collection, an expert appraisal ensures it’s reported accurately.

This step is also where you might discover hidden issues—missing assets, unknown debts, or conflicts among heirs. It can be emotionally draining, especially when it involves sifting through personal belongings or cleaning out a family home. But it’s crucial for full transparency.

Inventorying probate property also has tax implications. Knowing the estate’s total value helps determine whether estate taxes are owed. For larger estates, this step is monitored closely by tax authorities to ensure compliance.

Paying Debts and Taxes

After listing the assets, the executor’s next job is to settle the estate’s financial obligations. Before anyone inherits anything, all valid debts and taxes must be paid. This step is critical and legally required.

Here’s what it typically involves:

- Notifying Creditors: Most states require public notice (usually in a newspaper) to alert potential creditors. This gives them a window—often 90–120 days—to file a claim.

- Reviewing Claims: Not every claim is legitimate. The executor must verify debts and reject any that are invalid or lack proof.

- Paying Debts: Once verified, the executor pays off debts using estate funds. Common debts include:

- Credit card balances

- Mortgages and car loans

- Medical bills

- Utility and service bills

- Legal or accounting fees

- Paying Taxes: This includes income taxes owed by the deceased, property taxes, and possibly federal estate taxes if the estate is large enough. The executor may also need to file a final income tax return.

It’s important to note that creditors have a priority order. For example, administrative costs (like legal and court fees) usually come first, followed by funeral expenses, taxes, and then other unsecured debts. If the estate doesn’t have enough money to cover all debts, it becomes “insolvent,” and the court will guide how to distribute the limited assets.

No assets can be given to heirs until debts and taxes are fully resolved. If an executor skips this step or does it incorrectly, they could be held personally liable, so accuracy and diligence matter.

Distributing the Remaining Assets

Once the debts are cleared and taxes are paid, the remaining assets can finally be distributed to the rightful heirs and beneficiaries. This is the step everyone’s been waiting for, but it must be done in strict accordance with the will—or, if there’s no will, according to the laws of intestate succession.

If there is a valid will, the executor follows its instructions to divide up the estate. For example, the will might say:

- “My son gets the house.”

- “My daughter receives all bank accounts.”

- “The rest is split equally among my grandchildren.”

The executor must document every distribution and sometimes needs to get court approval before transferring ownership. This can involve retitling deeds, closing accounts, and physically handing over personal property.

In cases without a will, the law decides who gets what. This varies by state but generally prioritizes spouses, children, parents, and siblings. Sometimes, distant relatives inherit everything even if they never had a relationship with the deceased.

Disputes can arise here, especially if someone feels the will was unfair or if siblings disagree about who gets what. If this happens, it could lead to probate litigation, which can drag out the process for months or even years.

Before closing the estate, the executor typically prepares a final accounting for the court. This report shows every asset collected, debt paid, and dollar distributed. If everything is in order, the court issues a final discharge, officially closing the probate case.

How Probate Property Is Valued

Valuing probate property is an essential part of the probate process. It helps determine the estate’s total worth, ensures fair distribution, and plays a major role in calculating taxes and resolving disputes. Getting this valuation wrong can cause serious problems, from underpaying taxes to family fights over “who got what.”

The valuation process starts with creating an inventory, but it doesn’t stop there. Every asset must be given a dollar value. This is easier said than done, especially with unique or high-value items like real estate, antiques, or business shares.

There are a few common ways probate property is valued:

- Appraisals: For real estate, vehicles, and valuable collections, the executor often hires professional appraisers to determine fair market value.

- Account Statements: Bank accounts, investment portfolios, and retirement funds are typically valued based on the account balance at the time of death.

- Comparables: Real estate is often valued using recent sales of similar homes in the area.

- Expert Opinions: Businesses, intellectual property, or rare collectibles may require experts to give detailed reports.

Why is valuation so important? Because it affects everything from taxes to how assets are divided. For instance, if an estate is worth more than the federal exemption limit (currently in the millions), it may be subject to estate tax. Accurate valuation ensures these taxes are calculated correctly.

Executors are responsible for making sure valuations are honest and unbiased. If there’s a dispute over value—say one sibling thinks the family home is worth $500,000 while another says it’s only $350,000—the court may step in or require a new appraisal.

Valuing probate property isn’t just a number game—it’s about fairness, transparency, and legal compliance. It’s one of the trickiest and most crucial tasks in the entire probate process.

Role of Executors in Property Valuation

The executor plays a vital role in valuing probate property. Think of them as the manager of the estate—tasked with making sure everything is accounted for, valued correctly, and reported transparently to the probate court. Their decisions directly impact heirs, taxes, and the timeline for closing the estate.

One of the executor’s first major responsibilities is creating a detailed inventory of all the estate’s assets. But it’s not just about listing items—it’s about determining what they’re worth. For this, executors often hire professionals like:

- Certified appraisers for real estate

- Gemologists or antique dealers for jewelry and collectibles

- Accountants or valuation experts for business interests

Accuracy is crucial. Understating values can lead to IRS penalties or upset heirs, while overestimating can trigger unnecessary taxes. Executors must aim for the fair market value what the asset would sell for on the open market at the time of the decedent’s death.

But executors also face real-world complications. For instance, how do you value a home filled with sentimental items, like a decades-old piano or inherited china sets? Or what if the real estate market drops right after death? In some cases, alternate valuation dates may be used to adjust for changing conditions.

Executors are required to document all valuations and may need to file a formal report with the court. This is called an inventory and appraisal or a schedule of assets, depending on the state.

Moreover, the executor may need to communicate values to heirs—many of whom are emotionally invested in what they receive. Being transparent and consistent can help prevent disputes and maintain family harmony.

If the executor mishandles valuations—either through negligence or favoritism—they could be held personally liable. That’s why many choose to work with attorneys and financial professionals to get it right the first time.

How to Avoid Probate

Many people, especially those doing estate planning, aim to keep their assets out of probate entirely. Why? Because probate can be slow, costly, and public. It can tie up property for months, even years. Fortunately, there are several effective ways to avoid probate and ensure your assets pass quickly and privately to your loved ones.

Let’s explore the top strategies:

Establishing a Living Trust

A living trust is one of the most powerful tools for avoiding probate. When you create a living trust, you transfer ownership of your assets into the trust while you’re still alive—but you continue to manage them as the trustee.

Here’s how it works:

- You set up a revocable living trust and name a successor trustee.

- You transfer ownership of assets like your home, bank accounts, and investments into the trust.

- When you die, the successor trustee steps in and distributes the assets—without court involvement.

This bypasses probate completely. Since the trust, not you personally, owns the assets, they don’t become part of your probate estate. Plus, trusts are private documents—unlike wills, which are public once filed with the court.

Living trusts also allow for greater control. You can set rules like: “My daughter gets her inheritance in installments when she turns 25, 30, and 35.” This level of control is impossible through a standard will.

However, setting up a trust requires time and upfront cost—typically a few thousand dollars. But for many families, the long-term savings in legal fees and headaches make it worth it.

Using Joint Ownership and Beneficiary Designations

Another common way to avoid probate is through joint ownership. When you co-own property with someone—like a spouse or family member—it often includes a right of survivorship clause. That means when one owner dies, the other automatically inherits the property.

Examples include:

- Joint bank accounts

- Joint tenancy real estate

- Jointly owned vehicles

Also, beneficiary designations can be a probate-avoiding powerhouse. Assets like:

- Life insurance

- Retirement accounts (401(k), IRA)

- Payable-on-death (POD) bank accounts

- Transfer-on-death (TOD) investment accounts

…can all pass directly to named beneficiaries without a trip to the courthouse.

Just make sure these designations are up to date. If a beneficiary predeceases you or you forget to name one, the asset could still end up in probate.

Gifting and Other Strategies

Want to avoid probate and reduce the size of your estate at the same time? Consider gifting assets while you’re still alive. The IRS allows you to gift up to a certain amount per person per year ($17,000 in 2023) without tax consequences.

Here’s how gifting helps:

- Reduces the overall size of your estate

- Simplifies probate or potentially eliminates it

- Allows you to see your loved ones enjoy the gift now

Other lesser-known probate-avoidance strategies include:

- Lady Bird deeds (in some states): Allow you to transfer real estate upon death while maintaining control during life.

- Community property with right of survivorship: Available in certain states for married couples.

- Business succession plans: Help keep family businesses out of probate.

While these strategies are powerful, they must be executed properly. A mistake—like failing to retitle an asset into a trust or leaving a beneficiary form blank—can derail the entire plan.

It’s wise to consult an estate planning attorney to tailor these strategies to your personal situation. Because in estate planning, one size definitely doesn’t fit all.

What Does It Mean When a Property Is in Probate?

When a property is in probate, it means the owner has passed away and the property must go through a legal process to be transferred to the rightful heirs or beneficiaries. This process is known as probate, and it’s supervised by a probate court. The court ensures that all debts, taxes, and claims against the estate are paid before the property is distributed.

Let’s break it down. Imagine someone dies and owns a home solely in their name—there’s no joint ownership, no trust, and no named beneficiary. That home becomes probate property because there’s no automatic way for it to transfer ownership. Until the court officially approves the estate process, no one can legally sell, inherit, or even make changes to the title of that home.

Here’s what happens when a property is in probate:

- The executor (or administrator) is appointed by the court.

- The property is inventoried and appraised.

- Creditors are notified and debts are paid.

- The property may be sold if needed to cover debts or divide the estate.

- The court authorizes the final distribution of the property.

Probate is public, meaning anyone can look up information about the estate. This can make it an unattractive option for families who value privacy. Additionally, the process can take several months to over a year, especially if there are disputes or complications.

If the deceased left a will, it often specifies who gets the property—but it still has to be processed through the court. If there’s no will, state laws determine who inherits.

In short, a property in probate is “frozen” until the court gives the green light to move forward. It’s a protective process, but it can be time-consuming and expensive if not managed properly.

Can an Executor Sell Property Without Probate?

The short answer: No, an executor cannot sell probate property without going through the probate process unless specific legal exceptions apply.

The executor must first be officially appointed by the probate court. This involves submitting a petition, being granted Letters Testamentary (if there’s a will) or Letters of Administration (if there isn’t), and following the court’s instructions. Without this formal legal authority, the executor is just a named individual with no real power.

Once appointed, the executor can manage the estate’s assets, but even then, selling property often requires:

- Court approval (especially in formal probate)

- An appraisal or valuation of the property

- Notice to heirs or beneficiaries

- Following specific procedures, such as public sale requirements or court confirmation of the offer

There are exceptions. For example, if the property is held in a trust or was jointly owned with a right of survivorship, then it doesn’t go through probate, and the surviving party can manage or sell it directly.

But for solely owned assets, the executor has to wait. Trying to sell without probate is illegal and can lead to serious consequences—including lawsuits, title issues, and even criminal charges in cases of fraud.

If the executor tries to rush the process or skips probate, the sale might later be invalidated. That could cost buyers, heirs, and the estate thousands of dollars.

Some states offer simplified or expedited probate for smaller estates, which might allow for quicker action. But even in these cases, there’s usually still a court filing required.

In summary, unless the property is non-probate by design, an executor must have legal authority from the court before selling anything. Probate ensures that all sales are transparent, legal, and in the best interest of the estate and its heirs.

How Long Do You Have to Transfer Property After Death?

There is no single, universal deadline to transfer property after death—it varies by state, the type of property, and whether or not the estate must go through probate. However, certain timeframes and expectations do apply, especially once probate is initiated.

In most cases, property cannot legally be transferred until:

- The probate case is opened.

- The executor or administrator is officially appointed by the court.

- All debts, taxes, and claims are resolved.

- The court authorizes the final distribution of the estate.

This process typically takes 6 to 12 months for a standard probate case. In complex estates, or if there are disputes it can take years.

If the property is non-probate (like a jointly owned home or a trust-held asset), the transfer can happen much faster, often within a few weeks of submitting proper documentation, such as a death certificate and affidavit of survivorship.

Failure to act within a reasonable time can cause issues:

- Unpaid property taxes may accrue.

- Utility and maintenance issues may arise.

- Disputes among heirs may escalate.

Some states do impose time limits for opening probate after death. For example, California generally requires probate to be initiated within a year, while others may allow up to three years. But delays in property transfer can lead to complications in title, ownership claims, and tax consequences.

It’s essential for the executor to stay proactive. Delaying the transfer of property not only stalls inheritance but can also lead to penalties or higher legal fees. If you’re an heir, it’s wise to stay in touch with the executor and the probate attorney to ensure the process is moving forward.

How Long After a Person Dies Will Beneficiaries Be Notified?

Once probate is initiated and the executor is officially appointed, one of their key responsibilities is notifying all interested parties—including heirs and named beneficiaries. But how long does this take?

Typically, beneficiaries should be notified within 30 to 60 days after the court issues Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration. However, exact timelines vary by state law.

Here’s the usual process:

- Filing the will and probate petition with the court.

- Court schedules a hearing and formally appoints the executor.

- Notice of probate is mailed to all named beneficiaries and legal heirs.

- A public notice is also placed in a newspaper for potential creditors.

The notice must include:

- The name of the deceased

- The executor’s information

- The case number

- A statement of rights (e.g., the right to contest the will)

Heirs not named in the will must also be notified, especially in intestate cases. This helps prevent legal challenges and ensures full transparency.

If you’re a beneficiary and haven’t heard anything within a few months, you can contact the probate court directly or consult an attorney. Delays may be due to missing documents, court backlogs, or inaction by the executor.

By law, executors must act promptly and in good faith. If they fail to notify heirs in a timely manner, they can be held accountable and may even be removed from their role.

In short, beneficiaries should expect formal notice soon after the probate case is opened, usually within one to two months. The goal is to keep everyone informed and prevent surprises during the estate distribution process.

What Documents Does One Need to Prove Executorship?

To prove executorship legally and manage the estate, you need a few essential documents, whether you’re named in a will or appointed by the court. These documents give you the official authority to act on behalf of the deceased person’s estate.

Here’s a breakdown of the documents you typically need:

1. Death Certificate

This is the starting point. You’ll need a certified copy of the deceased person’s death certificate to file with the probate court. Most financial institutions and government agencies also require a copy before releasing any information or assets.

2. Original Will (if available)

If the deceased left a will, you must file the original with the probate court. The will names the executor and outlines how the estate should be distributed. The court must verify its authenticity before granting authority.

3. Petition for Probate

This legal form requests the court to open probate and appoint the named executor (or administrator, if there’s no will). It includes details about the deceased, their heirs, and an estimate of the estate’s value.

4. Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration

Once the court approves the petition, it issues Letters Testamentary (if there’s a will) or Letters of Administration (if there isn’t). These are the most critical documents—they officially authorize the executor to act. Banks, real estate agents, and courts will ask to see this before any transaction.

5. Identification and Bond (if required)

The court may request a valid ID or require the executor to post a probate bond—a type of insurance protecting beneficiaries from mismanagement.

Together, these documents legally establish your role and give you the power to:

- Access bank accounts

- Pay debts and taxes

- Sell property

- Distribute assets

Without them, you can’t legally manage the estate, and institutions won’t recognize your authority.

How to Claim Deceased Bank Accounts Without Probate

Claiming a deceased person’s bank account without going through probate is entirely possible—but only if the account was structured properly before their death. Otherwise, it likely becomes part of the probate estate.

Here are the most common ways to bypass probate for bank accounts:

1. Payable-on-Death (POD) Accounts

This is the easiest and most common method. If the deceased designated a beneficiary (you) on the bank account, you can claim the funds directly by:

- Presenting a death certificate

- Showing valid identification

- Completing a claim form at the bank

No probate is needed.

2. Joint Bank Accounts with Right of Survivorship

If you co-owned the account and had survivorship rights, you automatically become the full owner when the other account holder dies. Again, you’ll just need a death certificate and ID.

3. Small Estate Affidavit

Some states allow heirs to use a simplified affidavit process for small estates—usually under $50,000–$150,000 total. This avoids formal probate. Requirements vary by state but typically include:

- Waiting a specific time after death (e.g., 30–40 days)

- No other probate proceedings underway

- A sworn affidavit confirming your legal right to the funds

4. Trust-Owned Accounts

If the deceased placed the account in a revocable living trust, the successor trustee can claim it directly without probate. You’ll need the trust document and proof of your appointment.

If none of these apply, you’ll likely need to go through probate to access the funds. Always check with the bank and your local probate court for specific rules.

What Is Pre-Probate?

Pre-probate refers to the time period and actions taken before a probate case is officially filed with the court. It’s not an official legal term in most jurisdictions, but estate planners, attorneys, and realtors often use it to describe the early preparation phase of managing a deceased person’s affairs.

Here’s what typically happens during the pre-probate phase:

1. Gathering Documents and Records

This includes finding the will (if it exists), collecting financial documents, insurance policies, deeds, titles, tax records, and account statements. These are necessary for filing the probate petition later.

2. Notifying Family Members and Potential Heirs

This step helps set expectations and can prevent conflict. It’s also when families begin assigning roles—like who will be executor or administrator.

3. Securing the Estate

Before probate begins, it’s crucial to safeguard real estate, vehicles, and valuables. Locks may need changing, utilities managed, or insurance updated to prevent loss or damage.

4. Evaluating the Need for Probate

Some estates may not require formal probate. Pre-probate is when you assess:

- Is there a living trust?

- Are there POD/TOD accounts or jointly owned assets?

- Does the estate qualify for small estate procedures?

5. Consulting Professionals

Pre-probate is the ideal time to consult an estate attorney, financial advisor, or CPA. Getting expert input early helps avoid delays and costly mistakes once probate begins.

Pre-probate essentially sets the stage for what comes next. It’s like drawing up a game plan—gathering facts, organizing assets, and deciding the most efficient way to handle the estate. Proper preparation during this phase can save months of confusion and stress down the line.

What Is a Probate Listing in Real Estate?

A probate listing refers to a piece of real estate that is being sold as part of the probate process. This happens when a deceased person’s property needs to be liquidated (converted to cash) to pay off debts, divide assets among heirs, or fulfill the terms of a will.

The listing is typically handled by the executor or administrator of the estate, but it’s done under court supervision.

Here’s how it works:

1. Court Approval

Before a property can be listed, the executor must often get permission from the probate court. In some jurisdictions, they must also submit the listing agreement, appraisal, and marketing strategy.

2. Real Estate Agent Involvement

Most probate sales are handled by licensed real estate agents familiar with the process. These agents list the property on the open market just like any other home—but buyers are informed it’s a probate sale.

3. Appraisal and Pricing Rules

Courts may require the home to be listed close to or above the appraised value (often at least 90% of the appraisal). This protects beneficiaries and ensures the estate isn’t shortchanged.

4. Buyer Offers and Court Confirmation

In many cases, especially in formal probate, the court must confirm the sale. After an offer is accepted, a court hearing is held where other buyers can bid higher. This is called overbidding.

5. Disbursement

Once the sale is completed, proceeds go into the estate to pay off debts or get divided among heirs.

Probate listings can attract investors and bargain hunters, but the process can be slower and more complex than a standard sale. For the estate, it’s a practical way to turn inherited property into cash—but it must be done by the book.

What Are the Disadvantages of Probate?

While probate serves a necessary legal function, it comes with several well-known disadvantages that many families try to avoid through proper estate planning. Here are the key drawbacks:

1. Time-Consuming Process

Probate often takes 6 to 12 months, and complex cases can stretch into years. The court’s involvement, paperwork, waiting periods, and hearings significantly delay asset distribution. Heirs may be left waiting for months to receive property or funds.

2. Expensive Legal and Court Fees

Legal costs, filing fees, appraisal costs, executor compensation, and other court-related expenses can quickly add up. These fees are usually paid out of the estate—reducing what beneficiaries ultimately receive.

3. Public Record

Probate is a public process. Anyone can view the deceased’s will, list of assets, debts, and details about heirs and distributions. This lack of privacy can be uncomfortable for families, especially if there’s conflict or valuable property involved.

4. Greater Risk of Disputes

Because probate invites public scrutiny, it opens the door to challenges. Unhappy relatives or creditors can contest the will, argue over property, or delay proceedings, which adds stress and additional legal costs.

5. Limited Control Over Timing and Process

The court ultimately controls the timeline and steps. Even well-planned wills must follow court schedules. This limits how and when executors can distribute assets, sell property, or finalize the estate.

6. Frozen Assets

Until probate begins and court orders are issued, heirs cannot access or manage the deceased’s assets. This can cause problems with mortgage payments, property upkeep, or urgent financial needs.

These disadvantages are exactly why so many people choose to avoid probate by setting up living trusts, using joint ownership, or designating beneficiaries. Probate is not inherently bad—but it’s often more trouble than it’s worth if better planning could have prevented it.

Why Do Some Dislike the Probate Process?

Many individuals and families view the probate process with frustration or skepticism. While it’s a necessary legal safeguard, several factors contribute to why people dislike going through probate:

1. It’s Slow and Delayed

Probate takes time. Between court schedules, creditor notice periods, and paperwork reviews, it can be months before beneficiaries see any distribution. This can feel agonizing, especially during a time of grief.

2. It’s Expensive

People often associate probate with large legal bills. Attorney fees, court costs, appraisals, and executor fees are all subtracted from the estate. This can diminish inheritances significantly. In some cases, probate costs total 3% to 7% of the estate’s value.

3. Lack of Privacy

Probate is a public matter. Anyone can see the will, who inherited what, how much the estate is worth, and who owed money. For families who value discretion, this can be uncomfortable and even expose them to scams or unwanted attention.

4. Court Control Feels Bureaucratic

Even with a will, the court dictates how and when things happen. Executors must seek approval for major actions. Many families feel like the government is interfering in private family matters.

5. It Can Cause Family Tension

Probate can trigger disputes among family members, especially in blended families or where assets were unevenly divided. Arguments over who gets what can turn into lawsuits, dragging out the process and deepening rifts.

6. No Immediate Access to Funds

Until probate officially opens and the executor is authorized, no one can touch estate funds or property. This delay can create financial problems for surviving spouses or dependents.

In short, people dislike probate because it’s slow, expensive, public, and impersonal. With proper planning, it can often be avoided altogether, making life easier for those left behind.

How to Find Probate Properties

If you’re an investor, real estate agent, or buyer looking for unique opportunities, probate properties can be goldmines. These properties are often sold below market value because the heirs want a quick sale to settle the estate. But how do you find them?

1. Check County Probate Court Records

Most probate cases are public. Visit the probate division of your local courthouse (or its website) and search for open estates. You can find:

- Names of deceased persons

- Case numbers

- Executors or administrators

- Property assets listed

Some counties even list homes being sold as part of an estate.

2. Work with Real Estate Agents Who Specialize in Probate

Many agents specialize in probate listings and understand the legal nuances. They often have access to MLS filters or courthouse contacts that allow them to spot upcoming probate sales quickly.

3. Search Online Probate Listings

Some websites and platforms (especially those geared toward investors) offer probate property leads. You can subscribe to services that compile public records into searchable databases for your area.

4. Attend Estate Sales or Auctions

Some probate sales are handled through public auctions. This can be a good chance to buy directly from the estate or from the court if it requires a competitive bidding process.

5. Build Relationships with Probate Attorneys

Attorneys handling probate cases often have early knowledge of properties that will be sold. Establishing relationships with them may give you access to off-market opportunities.

6. Use Keywords in MLS Searches

Look for listings marked as “estate sale,” “probate sale,” or “subject to court confirmation.” These are often properties tied to probate proceedings.

Keep in mind, probate purchases can take longer to close and may require court approval, so patience and due diligence are key. But for many buyers, the discounts are well worth it.

Can I Sell My Deceased Parents’ House Without Probate?

Selling your deceased parents’ house without going through probate depends on how the title was held and what estate planning they did. In many cases, you cannot legally sell the house until probate is completed, but there are important exceptions.

✅ You CAN sell without probate if:

- The house was jointly owned with right of survivorship

If your parent co-owned the property with a spouse or someone else, the surviving owner automatically takes full ownership. Probate isn’t needed—just file a death certificate and affidavit with the county. - The home was placed in a living trust

If the house was in a revocable trust, the successor trustee can manage or sell it without probate. This is one of the most efficient ways to avoid delays. - You have a Transfer-on-Death (TOD) deed

In some states, your parent may have filed a TOD deed that automatically transfers property to a named beneficiary upon death. No probate is needed.

❌ You CANNOT sell without probate if:

- The property was solely owned by the deceased.

- There’s no trust or TOD deed in place.

- The title lists only your parents name and no survivorship clause.

In these cases, the house becomes probate property, and only the court-appointed executor or administrator has the legal authority to sell it. You’d need to:

- File for probate

- Be granted Letters Testamentary or Administration

- Get court permission to sell

Selling the property without proper authority can void the sale, create legal issues with the title, and open you to lawsuits. Always check the deed, consult a probate attorney, and follow your state’s legal process before listing the home.

Conclusion

Probate property might sound like legal jargon, but it plays a huge role in how a person’s estate is managed after death. Whether it’s a house, car, jewelry, or a bank account in your name only, these assets become part of the probate estate unless you’ve taken steps to transfer them outside the court process. Understanding the difference between probate and non-probate property can save your family time, money, and a lot of stress.

The probate process itself isn’t necessarily a villain—it exists to protect everyone involved. But it’s often slow, expensive, and very public. That’s why estate planning strategies that avoid probate like setting up a living trust, using joint ownership, or naming beneficiaries, are so popular.

If you’re an executor, understanding how to identify, inventory, and value probate property is key. Mistakes can lead to legal trouble or family conflict. And if you’re planning your estate, knowing what counts as probate property can help you create a smoother, more private, and more efficient path for your loved ones after you’re gone.

In the end, probate property is about more than legal definitions—it’s about legacy. With the right planning, you can make sure your estate is passed on thoughtfully, respectfully, and without unnecessary hassle.

Frequently Asked Questions About Probate Property

Does having a will avoid probate?

No. A will outlines how you want your assets distributed, but it still goes through probate unless the assets are placed in a trust or have other probate-avoiding structures.

What happens if someone dies without any probate property?

If there’s no probate property, there may be no need to open a probate case. Assets like life insurance or jointly owned property transfer directly to the named beneficiaries.

Can personal items like jewelry or furniture be considered probate property?

Absolutely. Unless they’re specifically listed in a trust or gifted before death, personal items are part of the probate estate and must be accounted for in the probate process.

How long does it take to settle probate property?

It varies by state and complexity, but the average probate process takes 6 to 12 months. Complex estates or family disputes can drag it out for years.